The History of the

Figh Pickett Barnes School House

By James W. Fuller

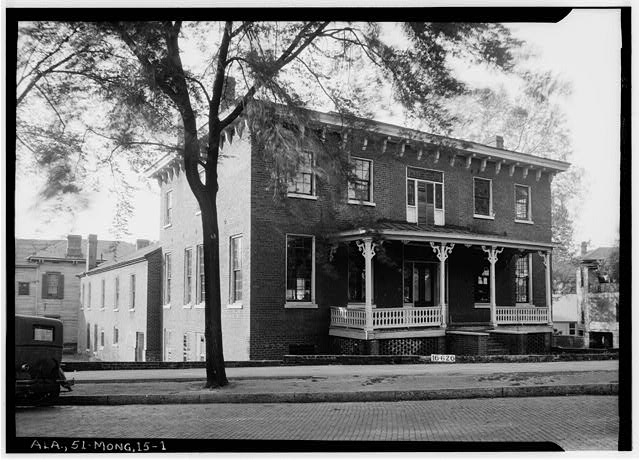

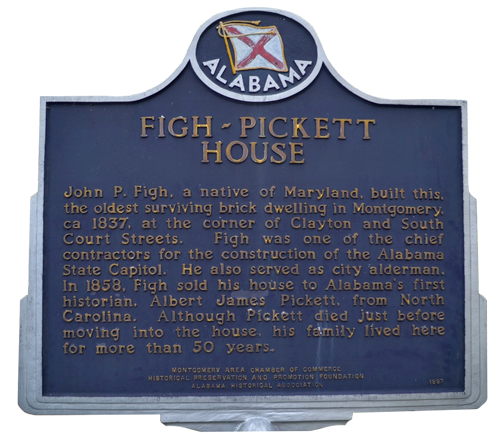

John P. Figh was a noted and well respected contractor in Montgomery, Alabama, and in or about the year 1837, determined to build a house for himself a few blocks from the center of town at 10 Clayton Street. We believe that he also owned and operated a brick yard and his house was one of the early ones here constructed of brick. At the time of its construction, the town was not much over twenty years old, and the earliest dwellings and businesses were log construction. We imagine that some of these still existed in that year. His house is now considered the oldest brick one still standing in the city.

During these days, he was also the contractor of the bank building at Court Square that served for the Central Bank, and later the Merchants and Planters Bank, as well as the Farley National Bank and, in more recent years, the home of the jeweler, Klein & Son. Mr. Figh also built the house on South Court near Adams St. known as the Lomax House, and the Presbyterian Church on the first block of Adams in 1845-47. Only two years later, he built the State Capitol following a fire the previous year.

In 1858, he was approached by Col. Albert James Pickett, Alabama’s first historian, regarding the purchase of the Figh house. The colonel had published his outstanding “History of Alabama” in two volumes a few years earlier in 1852, and was living in Autaugaville, Alabama. Apparently suffering from poor health, he decided to move to town for the benefit of his wife. He purchased the house from Mr. Figh on October 14th and died on October 28th. His widow, Mrs. Sarah Harris Pickett, lived in the house until her death in 1894. Mrs. Pickett was the daughter of the wealthy Harris family, who owned a large plantation in what is now Highland Gardens and Chisholm. Some of her descendants later lived in Robinson Springs, and the Harris house there is still standing. One of the Harris’ who lived there was Mr. Chiles Harris, who was an outstanding educator at Lanier High School until the late 1940s. Another descendant of the Harris family was Julie Harris, actress of note, who died in 2013, and her brother, Richard Harris of North Carolina, with whom we have current contact.

During the War Between the States time, the Pickett family was “land poor”, as the expression went, necessitating Sarah Harris Pickett to take in “paying guests.” Many visitors to Montgomery were privileged to stay a few nights at the Pickett House. Among them were some prominent gentlemen such as Gen. Longstreet and Gen. Bragg.

This writer was privileged to know Gen. George Pickett of WWII. One day he visited the Figh-Pickett House and was given a tour of the house. When he saw the dining room, he said that his grandfather had told him that, when he was a child and visiting his grandmother, Sarah Harris Pickett, the dining room had the biggest table he had ever seen. The story is that the house had up to twenty bedrooms, and all of those folks needed to eat. Many bedrooms were lost in changes made to the wing on the rear of the house prior to the move to Court St.

In 1865, when word came to Montgomery that Yankee Gen. James Wilson was headed toward Montgomery from Selma, where he had done severe damage, Sarah Harris Pickett filled a trunk with books or bricks, something to give weight, and gave it to one of the slaves to take in the wagon out to the plantation. When Wilson’s Raiders, as they were called, arrived at the Pickett door, they searched the house for silver and other valuables. Not finding any silver, the slaves were questioned as to the whereabouts of the silver. Thinking that what they had taken away in the trunk was the silver, the slaves replied, “They done gone to the plantation.” Actually, it was not in the trunk, but the silver was hidden in the cupola of the house above the attic. So it was saved and used by family descendants until the 1950s, when it was stolen by gypsies in New Jersey, where some descendants were living. Only a nice sized plated tray, engraved with the name PICKETT, was left, and it is now in the possession of the Society.

Following Mrs. Pickett’s death in 1894, the house has served in many different ways.

The first two owners of the house were of fine prominence, but the next played an equally important role in Montgomery history. Professor Elly Barnes, already known for his superior talents in educating young people in central Alabama, moved his school from Highland Home to Montgomery in 1897 and, after locating in several locations, purchased the Figh-Pickett House from the Pickett family in 1905. He opened his Barnes School for Boys in 1906, after considerable alterations by the Hugger Bros. Construction Company to adapt it for use as a school. The large room that originally contained two parlors, a bedroom and a library became ”The Big Room”, as it was known then. It is preserved and now serves for large meetings of the Society.

The lower four grades were taught in one room by a female teacher very much like earlier schools operated. The fifth through twelfth grades were in the Big Room, and moved to classes upstairs in the old bedrooms. It prepared many young men in the community for successful careers in life, with heavy influence toward a classic education. The school continued until the end of 1942, when the younger teacher’s deferments from WWII expired at the end of the school year, and they were drafted. Mr. Elly and the other older teachers decided to close the school. A reunion of Barnes Boys was held around ten years ago, with maybe 20 present then, and now no more than a handful are still living.

Since the Barnes School for Boys closed, the house has served as a boarding house operated by several other families, a Methodist church, a Packard and Edsel dealership, a naval supply store, a Sherwin Williams store, a 7-11 convenience type food store and finally an insurance company.

In the late 1900s, the Federal Government found that the existing post office should be moved to a new building and the old post office and Federal Court facilities on Court St. should be considerably enlarged. This meant that the site of the Figh-Pickett House would be a problem, since it was in the way of the construction. Later, we were told that we might keep the house on the campus of the Federal complex in its same location. When the unfortunate Oklahoma City tragedy took place, Janet Reno, at that time the Attorney General, ruled that the plan for the Montgomery project could not include the house on the campus because it might create a security risk for the Court House.

Thus began a search for a lot on which to move the house, since it had to be either demolished or moved as decided by the Federal judges of that court. But, because of its size and weight, it must be moved within a reasonable distance. Aside from the fact that the Society had limited funds with which to purchase a lot, the search extended as far away as Hull Street and Coosa Street. The problem was that the house, wider than most streets, would require that the trees and power poles be cleared on at least one side to gain clearance. In some instances, the moving house only cleared the front porches of houses it passed by a few feet.

Just when it looked as if the situation was beyond solving, our president at that time, George Mark Wood, had a visit from a friend, Bobby Arrington. He came in and sat down in George’s office and said he had a problem. George sympathetically said, “How can I help, Bobby?” He replied that he owned his grandmother’s property on Court Street at the corner of Mildred. He had the house torn down, but was still saddled with the taxes every year and could find no buyers. He further stated that he would do anything to unload the lot. George said in as calm a voice as he could muster, “Bobby, I may just have a solution for you. “That was a glorious day.”

The wheels then started turning on how to get the house from Clayton St. to Court St. Since the Government had caused the necessity of moving the house, then they should bear the expense of the move. By golly, they agreed! Now came the task of deciding how we could afford to buy the house from Uncle Sam since he had bought the house from the previous owner, the New South Insurance Co. We had lunch at the Young House where the Board was meeting in those days. Much discussion was voiced with the representative of the General Services Administration, the government agency in charge of real property and construction. We had not been able to arrive at a figure suitable to both sides. Bubba Trotman, one of the Board members asked how much money do we have in the bank? The one that knew said about $9,000 dollars. Bubba quickly said to the Government guy, “How about $9,000 dollars?” Understand, we had not voted on this proposal, Bubba just blurted it out. The GSA guy, Andruzak, looked around the room slowly, looked at the floor and after a minute looked up and said “OK.” And that was that. Some of us were thinking, “What the hell have we done.”

When the possession of the house came to the Society, next came the problem of how to move the house. We called Columbus, Ga. and talked to the Historical group there and asked about house moving contractors. Nothing there. Next we called the Savannah Historical Foundation, and they were quick to say yes, there was a man there that was really special, and he was a past master at house moving and, yes, he had moved brick houses. His name was Ramsey Khalidi. He proved to be an accomplished person and, as we found out, a master of his trade. He was over here soon talking about how the move could be facilitated. He was able to be the go-between guy who worked with the GSA, their government official and the insurance company who owned the house and us.

It would take many months to prepare the house for the move, and there was also the design for clearing the street of trees and power poles. Ramsey dealt directly with the government for his contract, so we did not have to face that dilemma. I would guess the cost was over $400,000, including $85,000 to the Power Company for the cost of removing a block and half of power poles and lines. The pole at the corner of Clayton and Court, where the Capital Towers (formerly Walter Bragg Smith) Apartment building is located, is what is known as a “sacred pole”. That means it cannot be disturbed, as the power supply feeds all of west Montgomery. But the tenants in the apartments would be without power, and were notified ahead of time to either be prepared to remain in their apartment for the day without AC or spend the day out. Some took up the offer that a supply of cold beer would be found down at the swimming pool.

The next step of preparing the house for its move was very technical, and I will try to give a simplified version. It would not have been reasonable to take the complete house, including the foundation, as one unit, because the cost would have made it impossible. Square openings were cut in the brick walls approximately a foot square and four feet apart, and the same on the opposite wall Then, the same on the other two walls, but just under the first openings. One foot square “I” beams were inserted all the way through the house and coming out the other wall. The other beams were inserted through, just under the first set, and then finally another set of holes through the first wall so that you had three sets of beams in opposite directions resting on each other, forming a rigid grid foundation. With the addition of the one hundred tons of steel beams to the house, the total weight resulted in just under 600 tons. This, of course, was too much weight to be carried on any vehicle, so dollies with a total of 96 wheels were placed under the house and heavy steel cables were attached to three heavy duty automobile type wrecker trucks. They were tethered to three dump trucks loaded with rock with chocked wheels. The point being that the pulling arrangement had to weigh more than the house, or the house would have pulled the vehicles.

The wheels under the house had to be adjusted constantly, since they were guiding the house. This meant that a major part of the work was done under the house while it was actually moving. After some nervous moments, everyone soon forgot that they had 586 tons moving over their heads. As a matter of fact, since it was in July, the crew gathered in the shade of the house to eat their lunch. The moving was extremely slow, and the only way you could tell it was actually in motion was to watch the tire treads to see that it was actually going forward.

It took three days to go three blocks because it could not be rushed. Many interested citizens watched the slow progress with great interest. Some spectators would come during the night to see how far it had gone, go home and sleep a few hours, and then return to check again. The last day started at the bottom of Court Street hill at 7:30 one Sunday morning, and arrived at the lot across from its final site at 4:30 Monday morning. It arrived on the lot face-forward, with the back to the street. The 96 wheels were reversed during the week, and the next weekend, it made its final trip across the street to its awaiting new foundation. Not an easy task since it would only move in one direction, forward. It had to center exactly, within an inch of its destination. Imagine parallel parking a 50 x 50 foot car that would only go forward. We did it first try. The shouts from all the crew were deafening.

Another historic event was scheduled for Court Street that day. The Atlanta Olympic flame bearers were to run down the street carrying the torch to Atlanta. The street was clear, and Mayor Emory Folmar was much relieved. He was heard making a statement earlier that sounded somewhat like a threat if the house was still in the middle of Court Street. However, there was not much he could have done with a 600 ton object centered on Court Street. The work continued through the night, with lights similar to those of a football field making it possible to continue like it was midday. During the next week, all of the wheels were reversed, and the house was backed over to its final spot the next weekend. If you will forgive a personal insert here, your writer was the only fool who climbed through the under-structure supporting the house to go to the second floor and wave from a window. There was considerable complaint from the Figh-Pickett House for being so rudely treated, with its groaning, popping and creaking. It was an exciting, once in a lifetime experience, which overpowered the terror. Several comments afterward included “Were you concerned that it would all collapse?” I thought, What a way to go! Quick.

After a few months of preparation, work began on the restoration. The bricks that were removed from the basement level walls that were left were cleaned and replaced on that lower floor by our bricklayers, to meet those suspended walls above on the first floor.

Not having the money to hire a construction company or architect, the Society formed its own construction company, with James Fuller serving as volunteer chief. It took a number of years to reach completion. The major part of the work of carpentry, brick work, concrete pouring and finishing, sheet rocking, installing windows and hanging doors, running electrical conduits, and painting were done by our crew. There were probably never over four men working at one time, and they did all of the major work. Of course, proper electricians and plumbers handled that part of the work, and the entire procedure was all done to code or better. Those who had a big part in that operation over the years were: Darrol Blair, our Number One Assistant, and Larry Chillous, Henry Dixon, James Perry, Billy Brown, Bob Canter, Kenny Thornton and James Fuller. Sam Butner, architect, assisted with architectural problems and the design of an arched gazebo covered with Confederate jasmine. It was Sam who joined me in support to force the government to lower the house 21 inches prior to being set on its foundation. It did not seem like much to make an issue over, but by so doing the house is now in a proper relation to its surroundings.

We were also assisted by a group of young students, high-school and college, from a Kentucky YMCA, who visited us during two summers. Their leader had made advance contact with non-profits here for free labor. It was great for us and they all had a ball traveling through the South helping the “needy”. This was an admirable program, and one that certainly could be copied in many community YMCA or church groups. I would imagine that their experience of giving of yourself for the benefit of others would be a lasting memory and influence.

One difficult problem we encountered involved the covering or removal of a very yellow paint on the exterior brick surfaces that unfortunately covered the beautiful natural brick from it’s 1837 exterior. This was left from its days as the location of a Sherwin Williams store. After experiments in attempting to remove the paint, and knowing that sandblasting would ruin the brick face, we determined the only way was to paint an area the color of the mortar and then hand paint each brick face by hand. It was a big success, and looks real now except where a bit of paint has pealed. After hearing the secret of our efforts, we had visits from other contractors to see the results that they could possibly apply to their restoration projects.

That is the story of the years of the old building we call home, and all of the work that lead us to a position of concentrating on the collection and preservation of the records of the past of our community. The entire restoration process took years, but it has made us very proud of our house, The Figh Pickett Barnes School House, Montgomery’s oldest surviving brick dwelling structure from 1837.